From Personal Data to Collective Power

“From Personal Data to Collective Power” is a main stage talk I gave at the 2018 MyData Conference on August 30. The talk connects the broad importance of collective action in the digital age to my work with Open Humans and my concern about what solutions the world will converge on for managing our personal data.

The talk is 27 minutes in length, and a written transcript of it is below.

I come with a variety of hats. I am a programmer, I’m a coder. In addition to my background in research, I have knowledge of human subjects research, and arcana around legal and ethical stuff that interests me. And I’m an advocate.

And so, with those warning labels, I guess I’ll get started.

When picking the title to this talk I wanted to start with “personal data” and go to “collective”, and I wasn’t sure about the last word. Do I want “power”? Do I want “good”? Do I want “action”?

What does matter to me is that “collective” element, because no person is an island in the environment of big data.

I say this in part because our data becomes entangled with others. But also because, as Dawn showed us, our data has meaning when it is contextualized in communities, compared to others. And also has power when it is aggregated.

And so, insistence on atomistic autonomy disempowers individuals - if we solely focus on empowering people on the individual scale, then we don’t fully realize power when the problems we face require collective action.

Those are not my words. Those are the words of Barbara Evans, who was writing about legal and bioethics issues around big data sharing in biomedical research. And biomedical research is great territory for learning lessons around the ethics of working with people who don’t fully understand and consent - and what is consent? And Evans in this piece is very critical of some of the models as being insufficiently empowering of people on that collective scale, and the way that we’ve tried to empower people is this atomistic approach.

And so I hope this here is a caution on how we think about we approach empowering ourselves with data, with personal data.

But what does collective action look like?

I mean - if we’re talking about technology and information - what do we mean?

Well, there’s a lot of different ways to look at that, a lot of different ways to slice it, but one way I’d like to put out here is examples of “peer production”.

One of these well known examples is “open source” and, in particular, Linux, which started as this grass roots project – where individuals start coming together – it’s not a traditional, financially motivated commercial product. And yet somehow it works, and Linux is now infrastructure. Like, the vast majority of the internet is running Linux, your Android phones are running Linux - it’s so much a part of the infrastructure that corporations have become heavily invested in it, and it is now a shared good. Not just on some sort of individual hobby project level, but on an economic level.

Another one is Wikipedia. And while with “open source” we’re talking about people collectively producing software, Wikipedia is open source, but what is collectively produced here is information. And this is the fifth most popular site on the web.

These are both examples of what Yochai Benkler calls “commons based peer production”, and Benkler’s an economist, and I think it’s important to call out that this is not just magic. He looks at these systems and he asks, as an economist, “How does that happen?” And also looks at the potential opportunities it creates. It creates an environment where by doing things collectively, one actually empowers individuals to have more autonomy. That they become more engaged and informed, and we hope that this may promote a more equitable approach.

It’s not the full solution, but when technology is collectively produced and collectively controlled, those are powerful things. It doesn’t come from magic. When we think about these grassroots efforts, you might think, “it just takes a lot of enthusiasm”. No, no, no. When he thinks about this, when other economists think about this, they think: what are the features you need to design a system that’s actually going to succeed in peer production?

Some of the success stories around peer production are around things like functional products. Wikipedia’s producing functional elements of information in articles. Another example is OpenStreetMap - it’s a functional product. And my personal data has a lot of functionality to it.

Modularity is important. People need to be able to contribute to this ecosystem in a way where they don’t have to contribute to all of it at once. They can contribute a very discrete module.

And importantly, the contributors - the stakeholders - the people that grow an ecosystem - should be anti-rival. The opposite of rivalrous. Where each person that contributes something new to that ecosystem benefits others, either in a diffuse manner, or in a specific manner because other specific stakeholders are benefiting.

So that’s the context I wanted to set up for Open Humans, which is this project that I lead and co-founded. And it was motivated from my background in research. I have spent years trying to help people share their data – get their data and share – for some altruistic purpose, for research.

Originally with genomes, but within genomes was a microcosm for other lessons in personal data. Genomes have meaning, they’re potentially identifiable, sensitive. Potential good can come from our understanding of them, from the individual scale for your own health to a collective scale of knowledge.

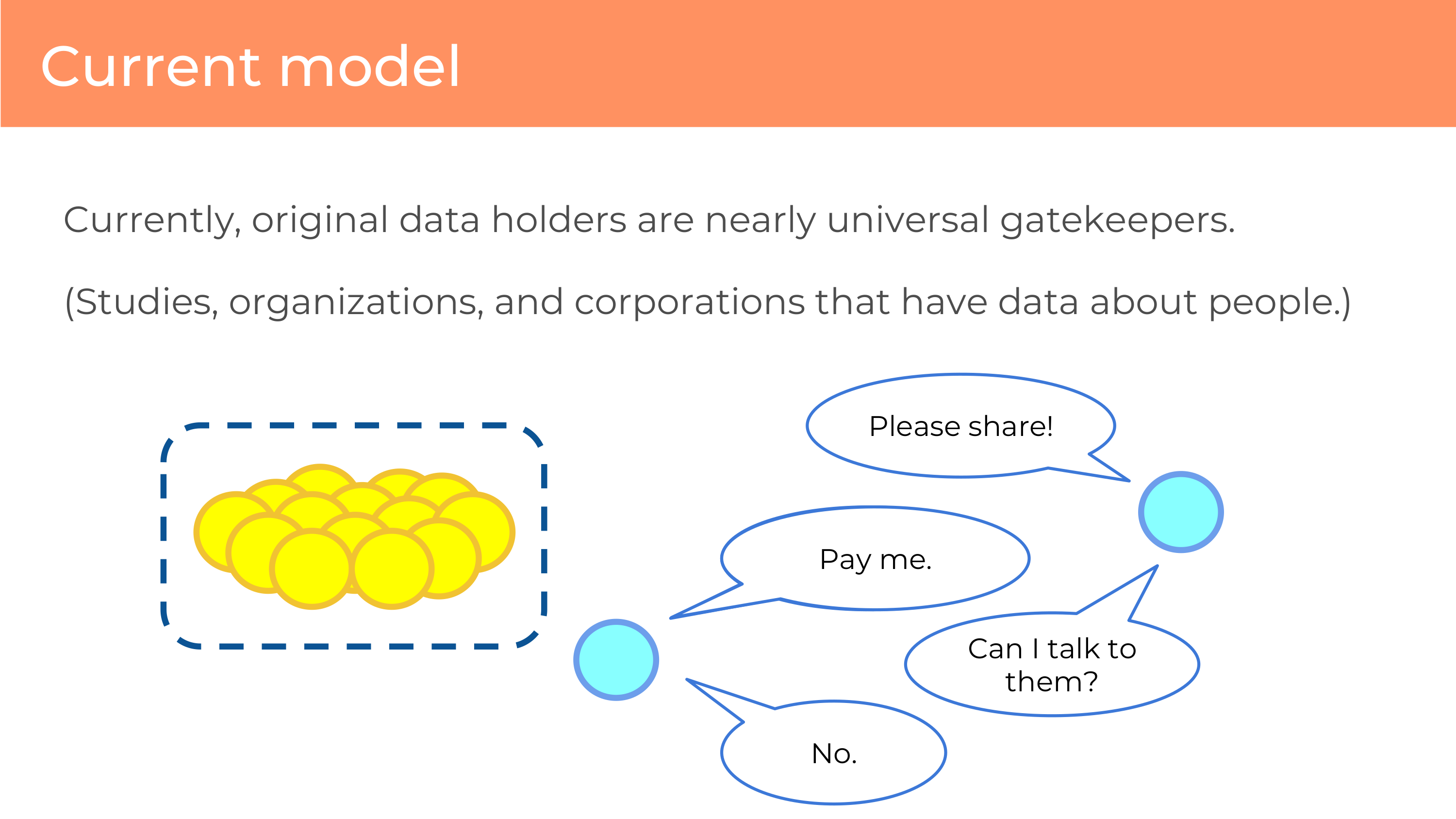

One of the problems that I saw in how we were doing research, that frustrated me, is that when we do research with personal data – like genomes – the original data holders are nearly universal gatekeepers. That can be a study that collected the data, or a corporation that has devices, or websites that are just scraping data about you.

And if you’re a researcher that has an interesting question to ask, you’re dependent on that relationship with the gatekeeper. And you can ask the gatekeeper, “Please share.” And the gatekeeper might say “No, I can’t violate privacy.” Or actually they might say something more like, “Pay me.”

Regardless of what their reasoning is – and they may have other reasonings as well – they are the decider. They get to decide whether you get to do a project that studies their data. It’s not our data. And that influences what is understood and what is not. They can discourage research that’s not convenient to them.

What’s worse is it’s very hard to add new data. Sometimes if you want to ask a question of the data, you need to add a little more. You need to ask one additional question – a survey question – you just want to say, “How do these little things that are easy to answer correlate to this data that you already have?” And the answer is almost always, “No” because that relationship with the individuals is of high value to the organization that has collected them. And I respect the value of those relationships, I see why they do that, but … it’s limiting.

So, how can we do better? What’s our alternative?

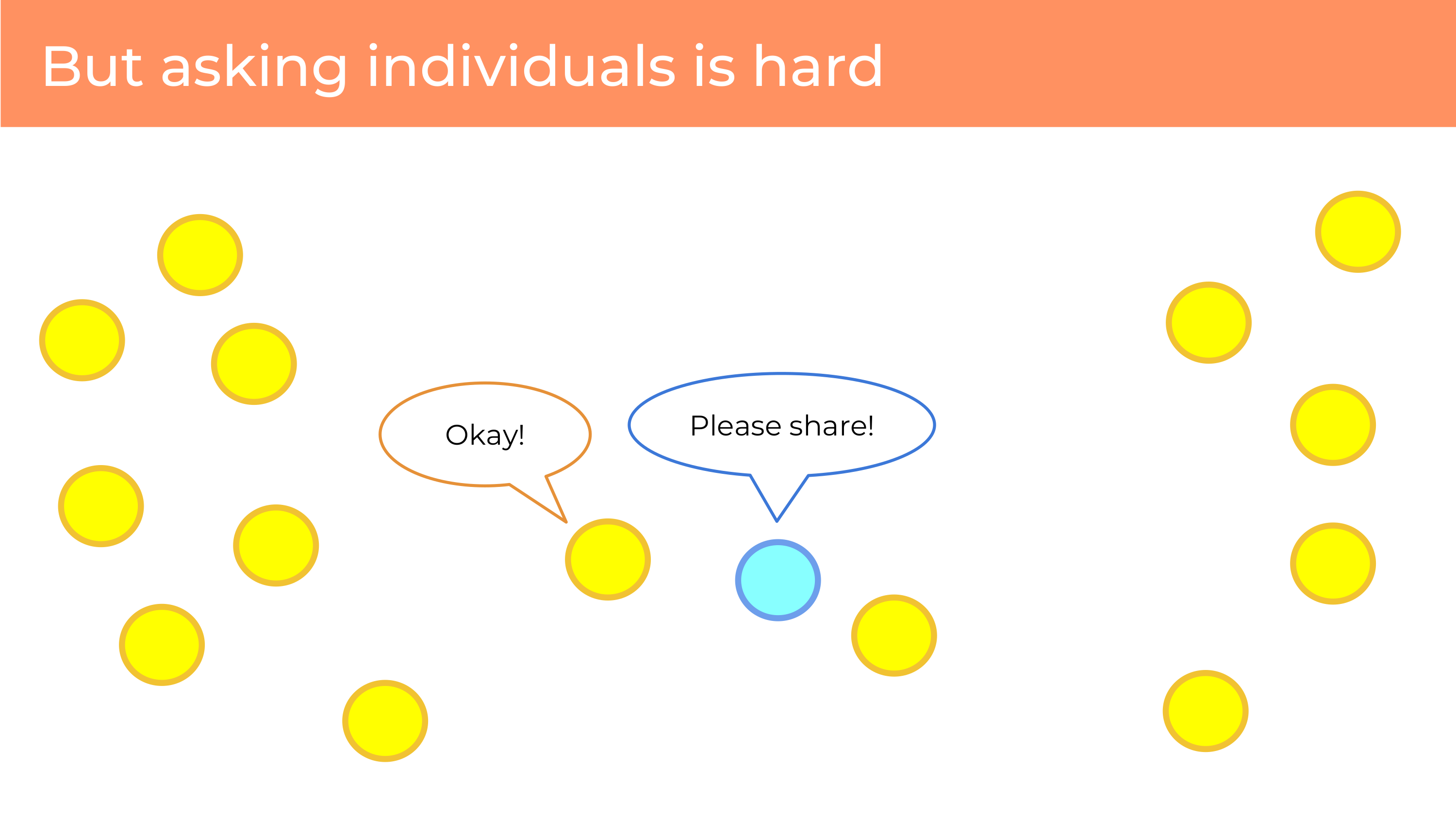

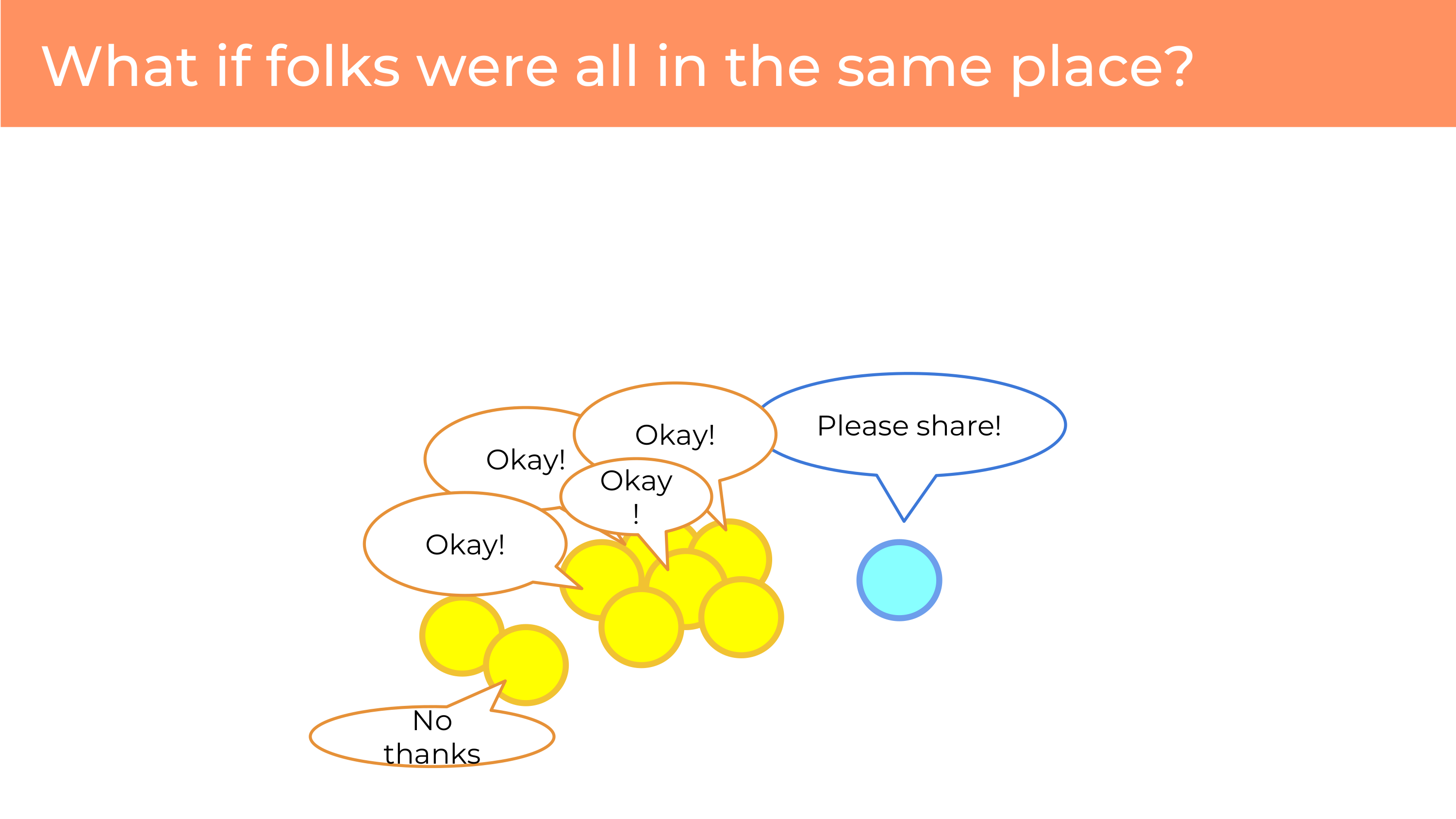

If I wanted to create a project to solicit that data I’d have to get out on the street, hold up a cardboard sign, say “Please share your data with my study.” I might get one or two people hearing me, but it’s hard to find people.

I think we’re more powerful if we can gather these people together. And then, when you ask, “Please share” you’re heard by many people - and you can hear a chorus of people responding to you.

And even better, some of them might say “No thanks.” And this is great because the decision is not being made for the group as a whole, and you can ask for things that might not have been possible if was something that you need to authorize for the whole group at once, where you end up in a “lowest common denominator” situation.

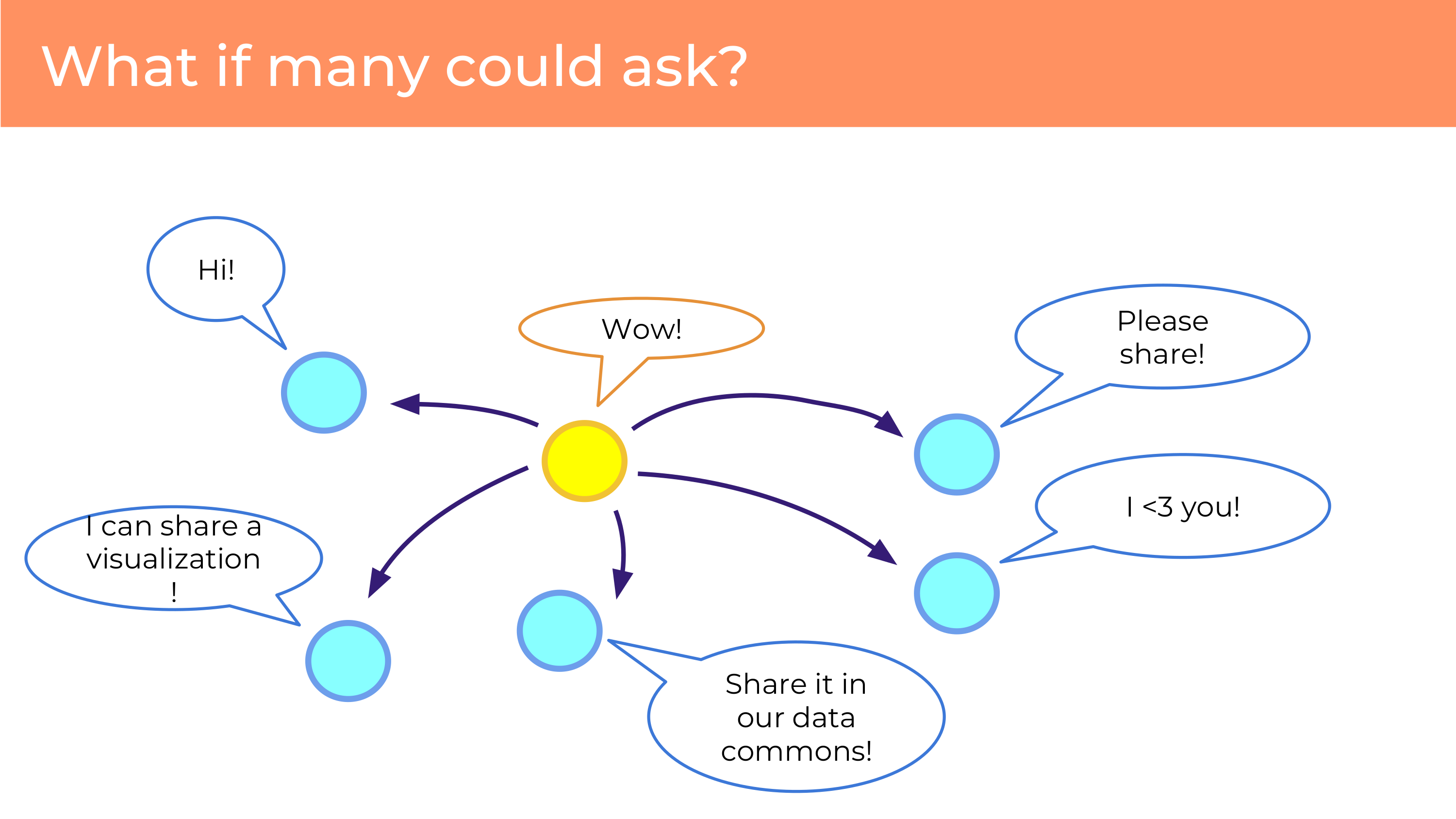

Another potential benefit that we might not realize when there’s gatekeeping with the data holders is that data’s not finite. What if many people could be asking? What if you made it easy? I think that if we gathered enough people with the right system, we can make it easy to authorize sharing with multiple places. When we focus a lot on how we’re going to manage data management or sharing with specific entities, we sometimes forget that we don’t need just one model, that I can share my data with this institution, and that project, and that data commons. And I don’t have to be exclusive. We don’t have to be putting our eggs in one basket.

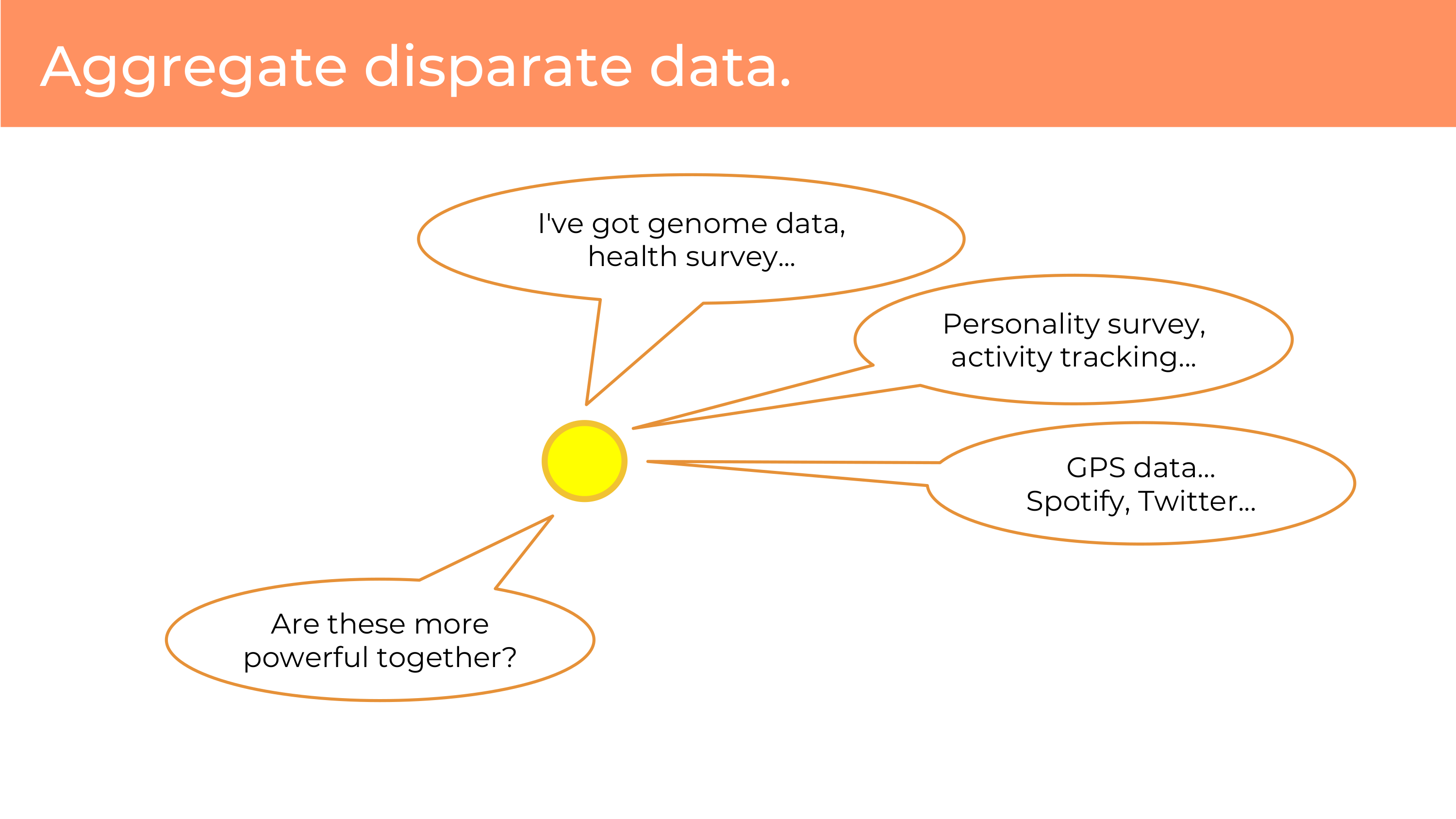

Data can be combined. This is something that those original data holders don’t get to do. You can aggregate through the individual disperse data, combinations that were not previously naturally occurring. You can take genome data and combine it with your Twitter data! I’m not really sure whether there’s any genetic variants predicting whether I’m going to use emojis – but the imagine might run wild here on things that we can combine, that we couldn’t combine before. You may be able to do new things that weren’t possible.

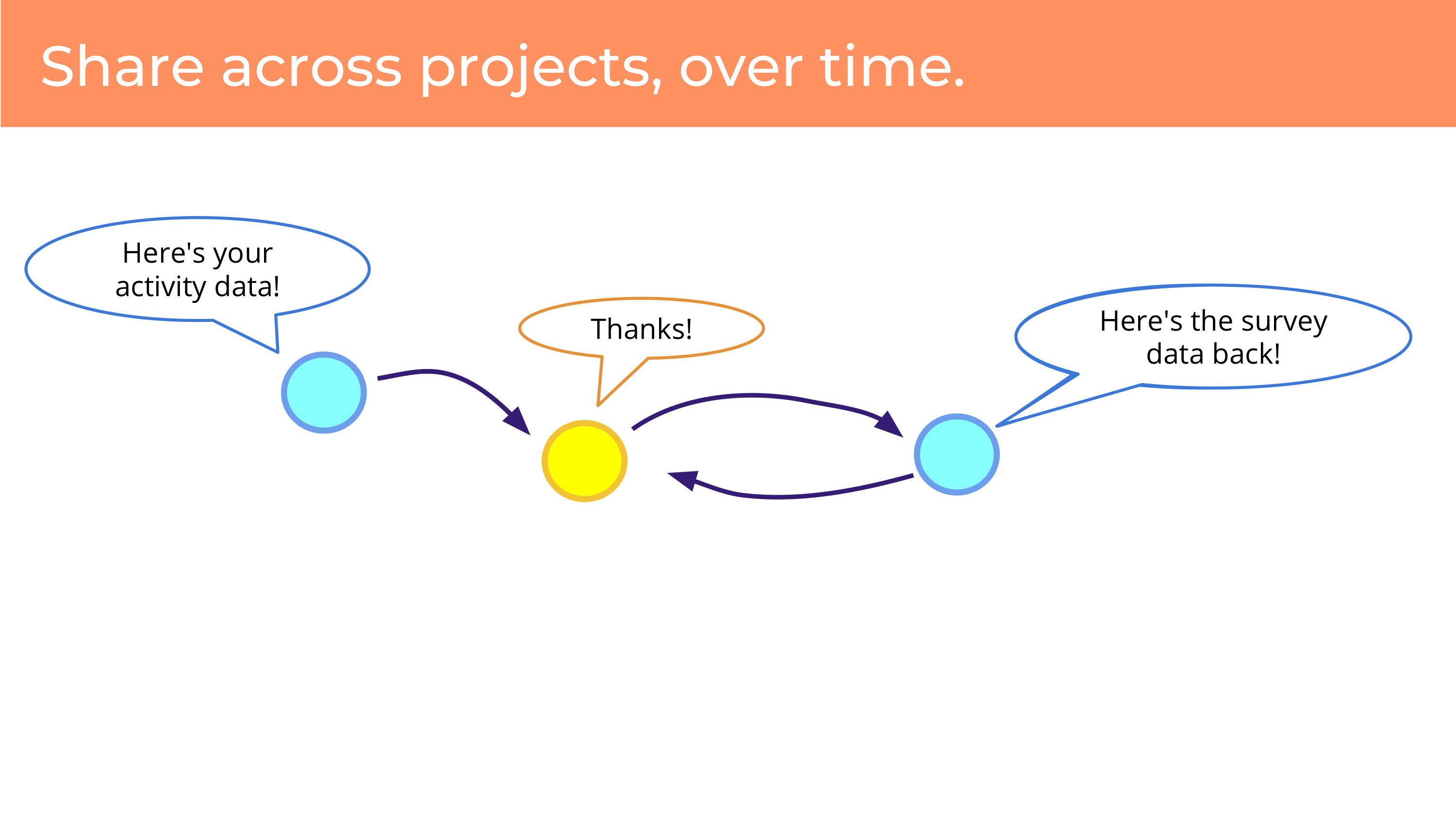

Finally, data can be alive. What I mean by that is, when I get a personal data set and I don’t have a connection to the person, and it’s not going to change, it feels dead to me. But if we have people and their data, and they have the ability to communicate with projects that they’re sharing the data with, that data can grow over time. And projects can contribute new data. So one project may share data, and another project may ask for it, and then the person may share it with that project – and then that project returns new data. So this is data that’s growing over time. Data can flow across projects. It’s not one project deciding what can be done with data or not. And data is living, you can ask new questions of someone, it’s making it richer.

So I think, broadly speaking, we can be more empowered by doing it together.

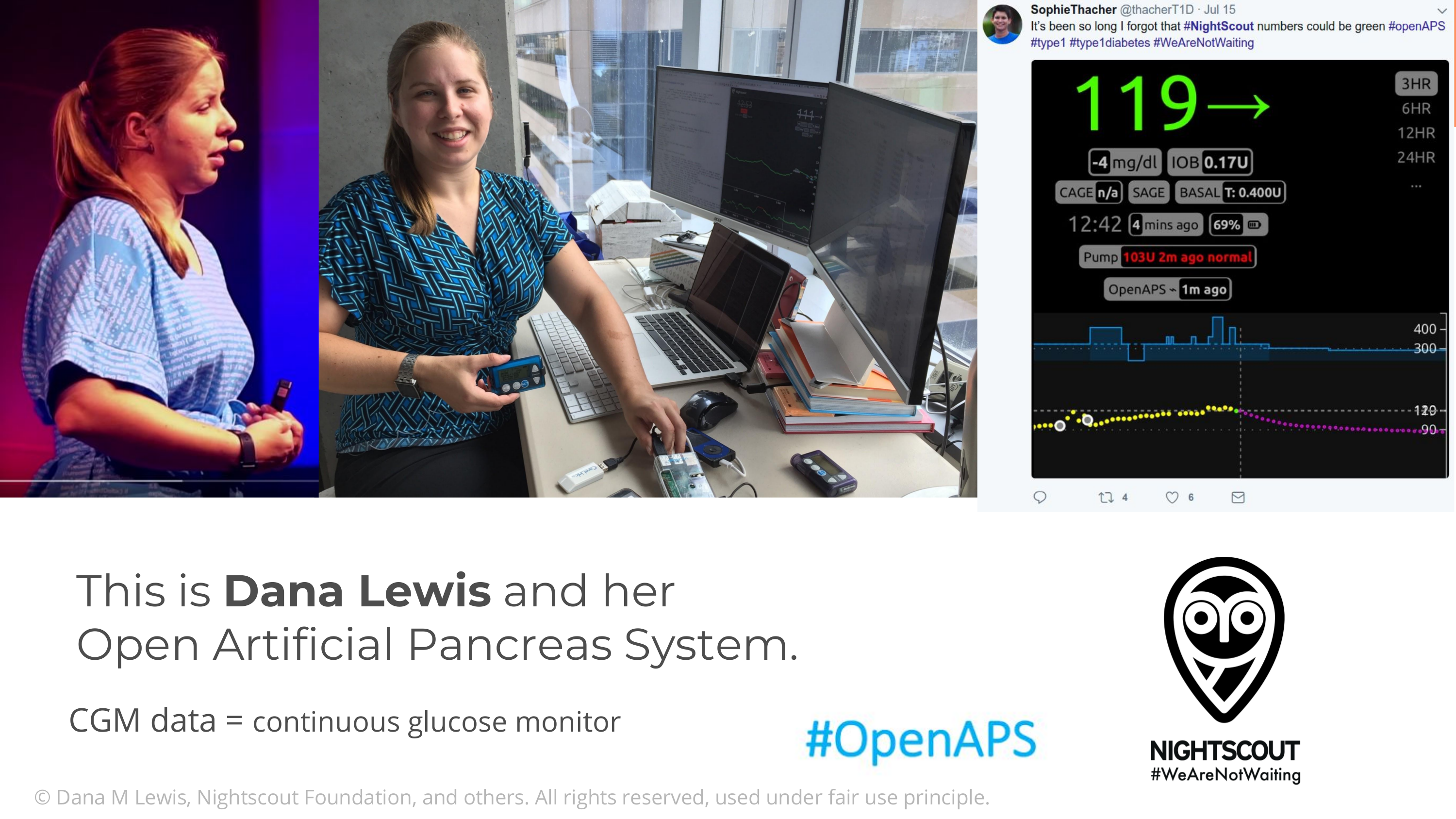

Now I’d like to get concrete with an example of how this system that we have, this platform, can be used to do research. In this case it’s research that’s very participant- or patient-led. It’s with someone who was here I think two years ago, Dana Lewis and the Nightscout community. Dana has type 1 diabetes and is a highly empowered individual. She’s part of a movement of people which starts with Nightscout data, an open source project to monitor continuous glucose monitoring data.

For type 1 diabetes patients this is very important data for them – one of the statistics that I didn’t know before becoming familiar with this community, is that there’s a lifetime risk of 1 in 20 of dying in your sleep with this condition, due to hypoglycemic shock. And Dana got into it because she’s a heavy sleeper, and she couldn’t get her device to make a loud enough noise when it goes hypo – and so she got involved by making a louder alarm, in this open source community, empowering individuals. And then, with her now-husband Scott, worked on making an algorithm – and then, closing the loop – so, using that data, they can automate an insulin pump.

I think there might be a member of this community in this room - Mikail, are you in here? No? I ran into him yesterday - and he’s using this device. He’s using the artificial pancreas system. So, we have an empowered user here at the event, I think he showed up on Slack. These are real people.

But the problem they face is: how do you enable community research? They have open source systems that they’re all running themselves, they don’t have collective data. So how do they aggregate it? And how do they manage data sharing? As a community, do they want to put all their eggs in one basket, one person that says “trust me” or one group or team? Those things can lead to uncertainty or politics – I don’t know that I would be comfortable picking one lead if I could have an opportunity to have something more flexible. Like – Open Humans.

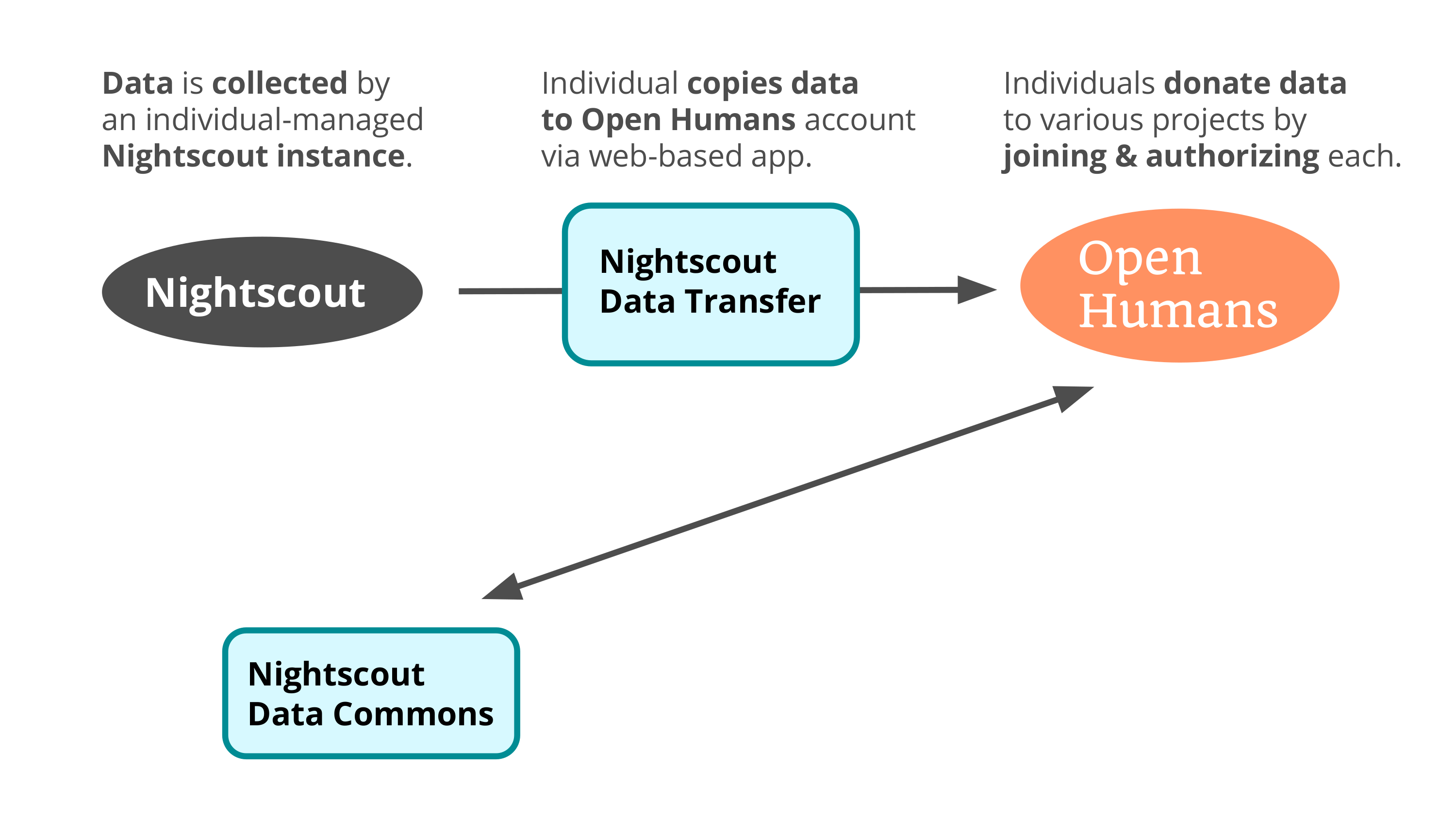

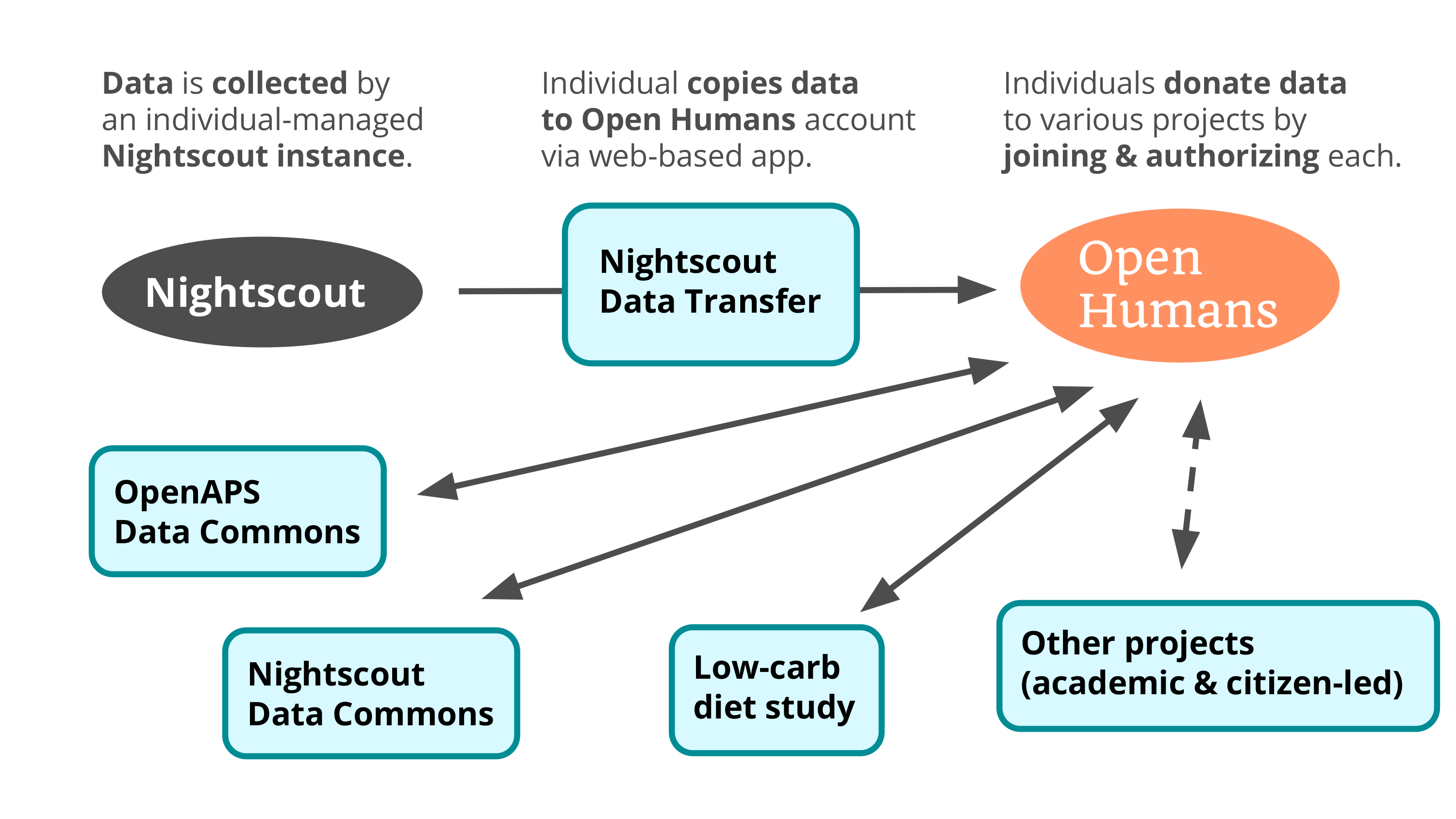

And so we were able to use Open Humans to support this process, by connecting their Nightscout server via a project that brings data into an account. And then a project was created called the Nightscout Data Commons – there’s a fairly large community of people who are just tracking their glucose data, they’re not doing the insulin pump thing – and that’s what the Nightscout Data Commons is.

But there is another data commons! So you can see right away that people can be donating their data twice. Why not? The OpenAPS Data Commons is specific to people using the full loop with the insulin device. And there’s almost a hundred people in the OpenAPS Data Commons. I don’t know if that sounds like a lot to you, but I asked Dana: how many people do you need to get a statistically significant sample? She’s working with researchers at UCSD, at Johns Hopkins, at Stanford… She said “20”. So I think nearly 100 is good news. It’s very rich data.

There’s also a study in the works associated with the broader Nightscout data, a collaboration with that community and a researcher at the University of Michigan, Joyce Lee. They’re working on the ethics review process, which is slow - but this is an experiment that the community wants to run, studying diet.

These things and more things become much easier now that there’s this system that’s collecting data and letting people join these different things, should they wish to do so.

What’s important to me about that last slide is the sense in which there’s not a single gatekeeper. That there’s not a single longitudinal study that’s deciding what this cohort can do, that now there’s many opportunities.

And this slide is my attempt to find a visual metaphor for how I feel about gates. Which is to say: I completely agree that the fence is kind of broken. And that gates are needed. I think that there’s multiple gates that can exist. But I also like to look beyond the construction of gates to other opportunities that we have.

I wanted to then come to one other concrete example, to think a little more about how we empower individual understanding.

Now one way in which I hope we can do this is by connecting Data Sense, I’ve been working with Dawn and people that work on Data Sense to try to connect that to Open Humans – because we have that ability to connect things with projects. It could just be another project that takes data and provides visualizations.

And I’m going to share something super-nerdy. Please endure a couple seconds of geek-speak at some point.

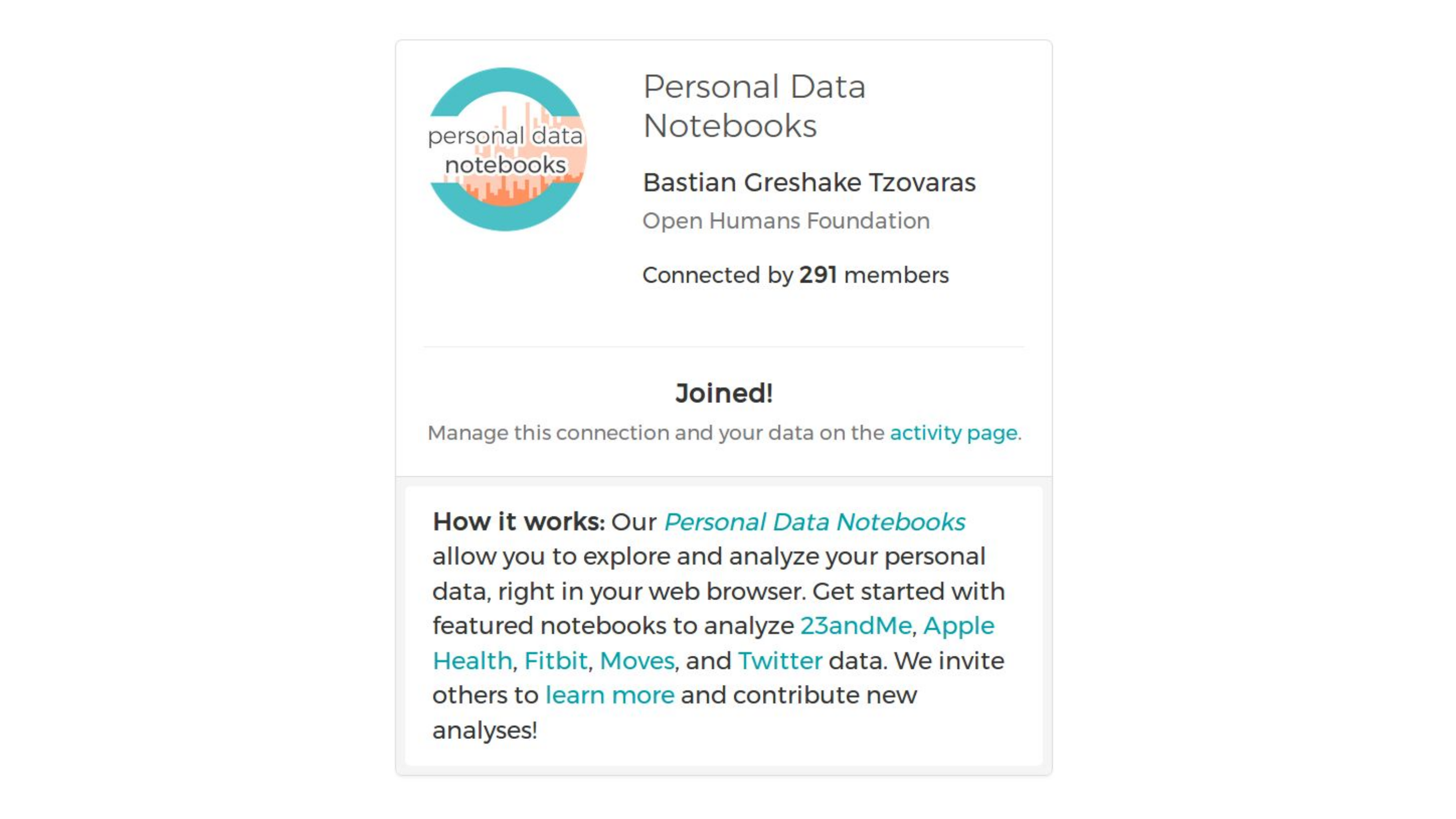

This is something that we recently launched called Personal Data Notebooks. I really love it because I think it’s reducing a lot of the friction around producing analyses of personal data and sharing them with others.

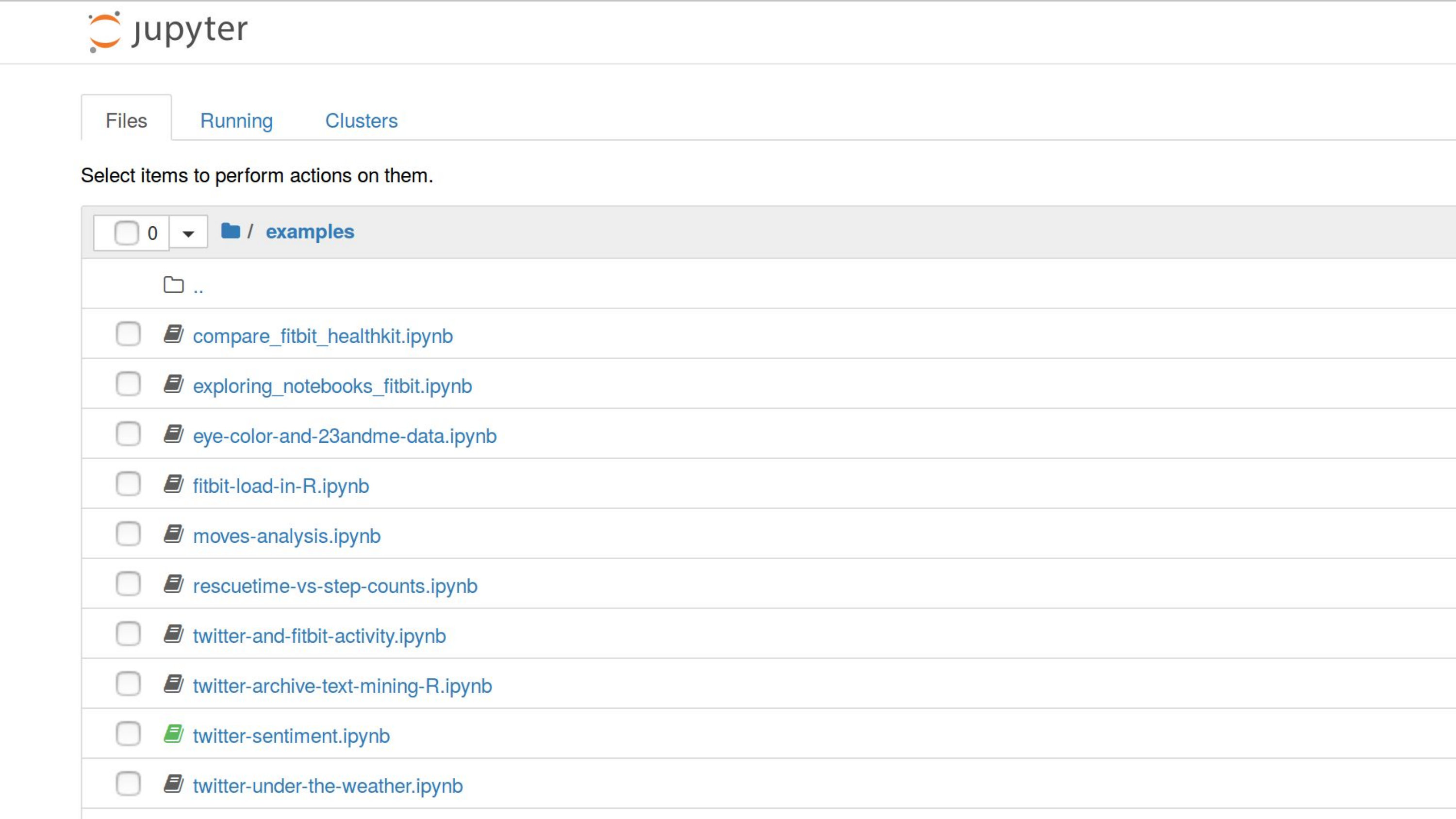

What it’s doing is – this is a Jupyter server – it’s using on the fly virtual machines to give people access to a Jupyter server which means that these things are “notebooks” on the screen, each line is a different notebook which contains code that you can run.

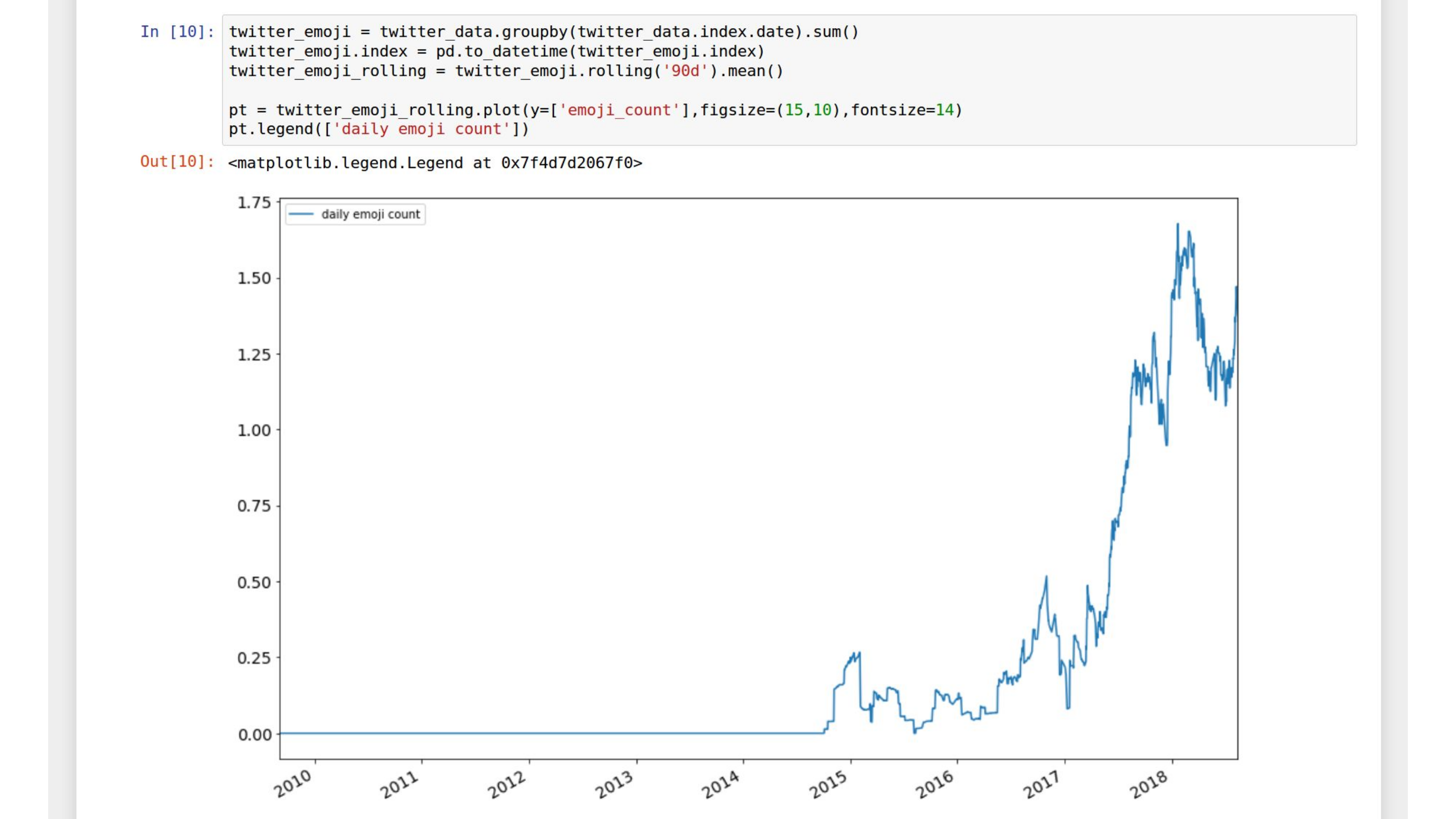

And the way that this is set up is that it has access to your data in Open Humans, this is your server, nobody else gets it. But you can run these notebooks, and you can share them – and you can edit them – or you don’t have to understand them! Like, here’s me running a notebook written in R.1 And this is me analyzing my Twitter data, we have support for Twitter data, and apparently… sometime in 2017, I really upped my emoji game. This is my emoji count.

This is written by someone else, the code is shared, and I can run it without understanding it. And I don’t have to share my data with him.

I love this little project because it creates a potential ecosystem for us for creating analyses, without needing the person that wrote the code doing the analysis for you, and it runs the code in a reproducible environment.

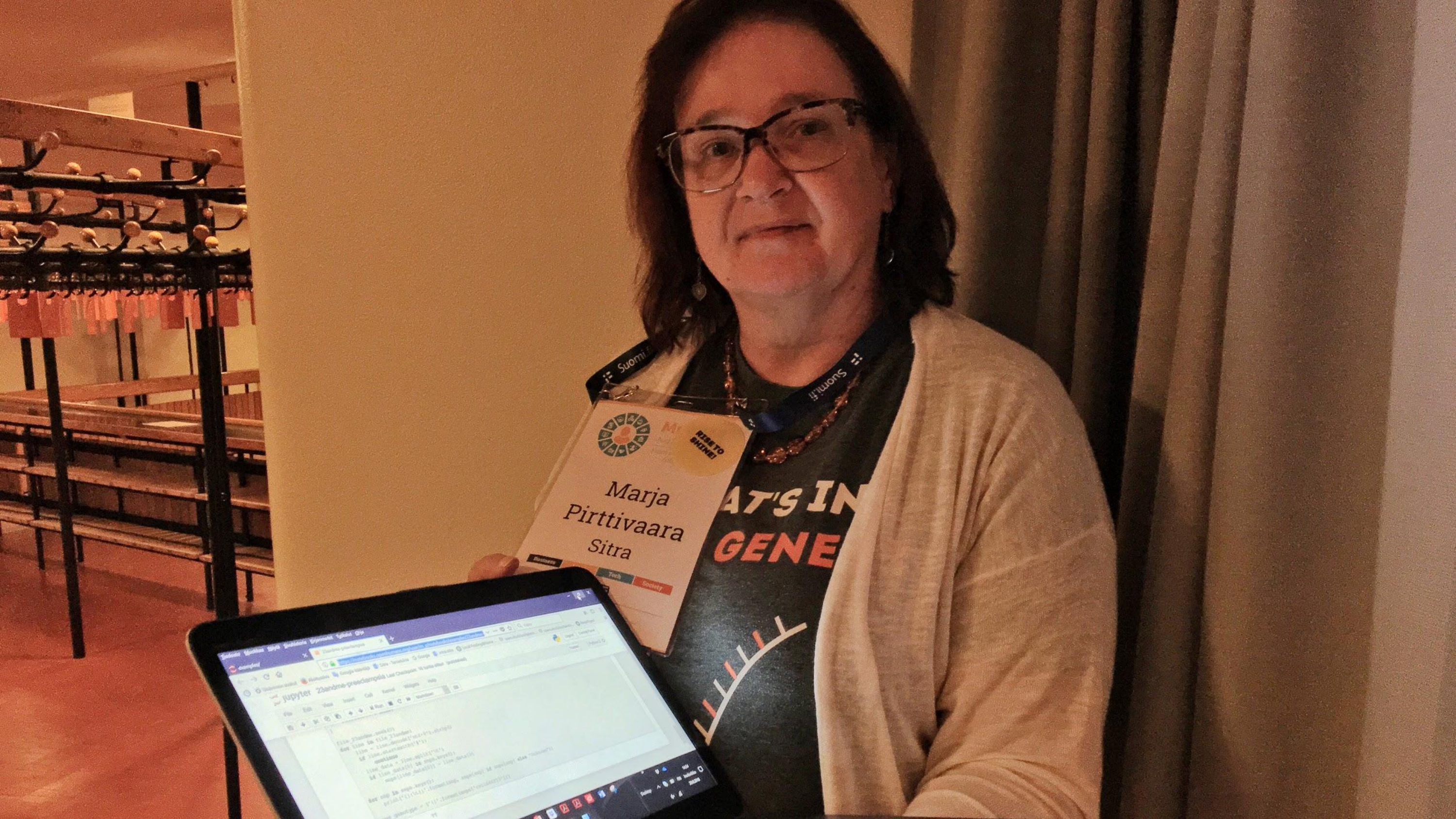

I wanted to wrap up my examples around Open Humans with another person in the audience. This is Marja – in the front right here – and Marja is super into genetics. And we hit it off the night before last in the bar, and Marja whips out her laptop and joins Open Humans. And then loads her genetic data. And then shares it with an analysis app – a side project that I have that creates a genetic data report. And then she opens up the notebook programs. And she runs a notebook analysis that I had written that does an eye color prediction, and I’m happy to see in the bar, hunched over drinks, it successfully predicted her eye color, that it’s blue or green.

And then Marja said, well how about we edit this, to look at a genetic variant that matters to me. And she’d already collected a list of these positions that mattered, for pregnancy risk factors, in particular for pre-eclampsia, which Marja had had. And so together we edited this code, just a couple lines, to instead look for that variant.

And then, clicked a button, and shared the new code. And when I got back to my hotel room I was able to run that code on my own data.

What I loved about this experience is that I found someone who enjoys their personal data, finds a lot of meaning in it, and in an evening at the bar – and not the entire evening, just a portion of this evening – we were able to go from not having known Open Humans to creating a new forked analysis code shared with the community that does something that Marja’s interested in.

And so with that, I’m going to zoom out, and try to think about the big picture again.

I’ve mentioned to you this thought about peer production. And when I talk about these projects that are adding data, or using data – either to spin up Jupyter servers, or do a visualization, or run a study, or do a citizen science project, or produce a data commons – there’s so many uses for that data. All of these things are modular, in an environment with functionality.

And I consider Open Humans, I hope, to be an environment that is potentially peer production, that each of these is producing anti-rival goods. That the community of people, and potential tools, and data sources, and opportunities to use them grow.

I think that peer production models are powerful, if the situation works. You can’t just do something enthusiastically and expect people to join you. I think it’s important not to be starry-eyed about it, but to think about how does one design an ecosystem to create a peer production environment. And if they reach critical mass – you need enough stakeholders, enough people doing so that other people start joining, they see it as a safe investment of their own time.

I want to make the point that what wins is not inevitable.

I don’t know that peer production solutions are always possible, or necessarily the right ones. But it’s important to think about what might win, right now.

Because Wikipedia didn’t have to be the winner in the space of producing modular, encyclopedic knowledge. It could have been something a little less community driven, and more commercial in nature, like Quora. Or, we didn’t have to have Facebook. We could have had something better.

But once something becomes infrastructure, it can be almost impossible to change.

And so I think that what we do now – the design of what we do now, and the technology, and the communities – matters.

1 It’s not R, it’s Python, which I’m proficient in – but apparently not proficient enough to realize it while preparing and presenting a talk!